Published December, 2021; updated November 2022

Section Editor: Molly Brett, MD3

Objective(s)

- Identify the appropriate screening and diagnostic tests for anxiety and depression

- Differentiate Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Unipolar Depressive Disorder from other behavioral health disorders that are managed differently.

- Construct a basic treatment strategy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Unipolar Depressive Disorder, including monitoring and follow-up timeline after initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy.

- Select the appropriate pharmacologic therapy for anxiety or depression based on key clinical features and patient preferences.

Teaching Instructions

Plan to spend at least 20-30 minutes preparing for this talk by using the Interactive Board for Learning/Preparing and clicking through the graphics animations to become familiar with the flow and content of the talk.

The anticipated time to deliver this talk is about 10-15 min without cases and 20-25 min with cases. It can also be divided into two separate talks.

The talk can be presented in two ways:

1. Project the “Interactive Board for Presentation” OR

2. Reproduce your own drawing of the presentation on a whiteboard.

With either method, we recommend printing out copies of the Learner’s Summary Handout which has the cases so they may have this for reference after the discussion.

Objective 1: Identify the appropriate screening and diagnostic tests for anxiety and depression

Why do we screen?

- Depression can often manifest as somatic symptoms and is easily missed. In fact, 50% of clinical depression is missed without screening

- Untreated depression is associated with decreased quality of life, increased mortality, and increased economic burden.

- Generalized anxiety and depression often co-manifest with a co-frequency between 39 and 62 percent

How do we screen?

Although the USPSTF does not offer a recommendation on frequency, they recommend screening for depression in adults age 18 and up. Typically, this is done at least once a year in a primary care setting.

Most Common Screening Tools:

PHQ 9 – Can be used to diagnose AND monitor response to treatment.

PHQ 2 – First two questions of the PHQ-9. Can be used as a “screening” exam.

GAD 7 – Can be used to diagnose AND monitor response to treatment.

PHQ 4 – First two questions of the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7. Used as a “screening” exam

BONUS: Other Screening tools (special situations)

Edinburgh Depression Screen – better for perinatal screening due to removal of somatic symptoms associated with pregnancy. Note: all pregnant persons should be screened during and after pregnancy.

GDS 5 – Good sensitivity and specificity in geriatric populations

NOTE: Familiarize yourself with your site’s practice for screening patients for depression and anxiety. Ask the group to describe their process for requesting MA/LPN to perform the screening, simple integrations in the EHR for entering the score or tracking it over time.

Objective 2: Differentiate Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Unipolar Depressive Disorder from other behavioral health disorders that are managed differently.

Familiarize yourself with the DSM-V criteria for both Unipolar Major Depression and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (listed below). Importantly, the diagnosis for both Unipolar Major Depression and GAD must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, cannot be caused by substance use or another medical condition.

Unipolar Major Depression:

Five or more of the following symptoms for at least 2 weeks (nearly every day). MUST have at least depressed mood or loss of interest. Bolded are non-somatic symptoms.

1. Depressed Mood

2. Loss of interest or pleasure in most or all activities

3. Insomnia or hypersomnia

4. Weight loss or weight gain or decrease/increase in appetite

5. Psychomotor retardation that is observable

6. Fatigue or low energy

7. Decreased ability to concentrate, think, or make decisions

8. Thoughts of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

9. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation, or suicide attempt

Subtypes of MDD (unsure if these are useful from a treatment perspective)

1. Depression with psychotic features

2. Seasonal Pattern

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Excessive anxiety and worry (more days than not) for at least 6 months about a number of events or activities.

- Difficult to control worry

- At least three of the following symptoms:

- Restlessness or feeling keyed up

- Easily fatigued

- Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

- Irritability

- Muscle Tension

- Sleep Disturbance

There are no firm recommendations to order routine screening labs. However, consider the following tests for new-onset depression or anxiety:

CBC – looking for Anemia as a cause for fatigue, low energy, poor concentration

TSH – especially if there is a family history of autoimmune or thyroid disorders.

HCG – To evaluate for a potential cause of mood disorders and inform the safest potential pharmacologic treatment.

BMP – If there is a concern for renal dysfunction and the potential need for renal dosing.

Objective 3: Construct a basic treatment strategy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Unipolar Depressive Disorder, including monitoring and follow-up timeline after initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy.

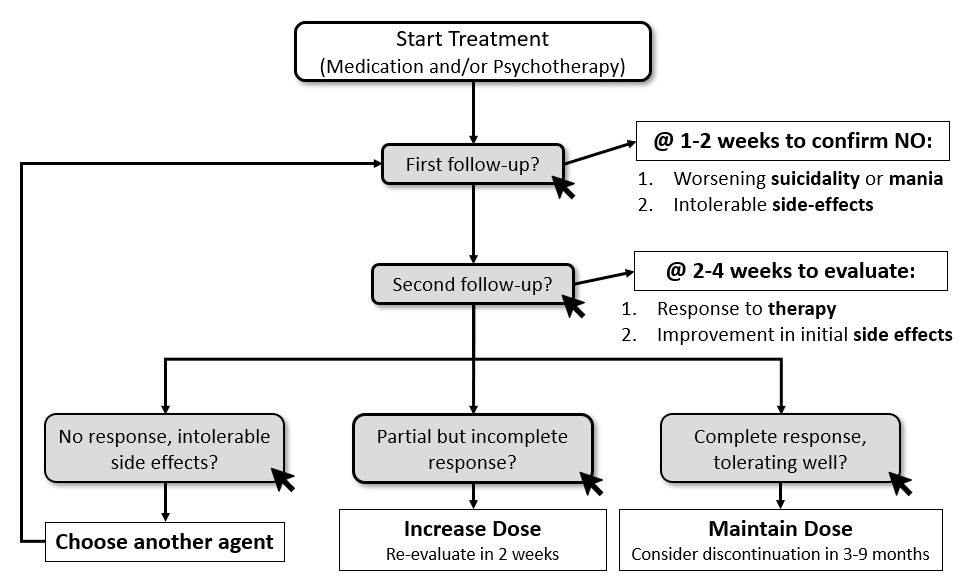

Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Unipolar Major Depressive Disorder share a similar treatment algorithm for first-line therapy, each with comparable response rates to medications or psychotherapy, and the combination is additive. This algorithm is based on recommendations from the American Psychiatric Association and the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

After identifying the patient's target for treatment and selecting a medication and/or psychotherapy based on patient clinical features, comorbidities and preferences, it is imperative that the provider establishes clear expectations for the intervention and plans for close follow-up to assess side-effects and response to therapy.

The first couple of weeks after initiating a new pharmacologic agent (especially for first-time treatment) are critical to a patient's safety and engagement. They may become suicidal or manic, or stop taking the medication due to undesired (but temporary) side effects or insufficient response. These negative outcomes may be prevented with a short-term follow-up with the prescribing provider, RN, or psychotherapist.

Many patients will ask about the timeline for discontinuation of these medications. While a trial of discontinuation is reasonable, recent research (N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1257) suggests that relapse and restarting antidepressants is common after discontinuation (though of note, relapse is ALSO common in patients who continue antidepressants). These meds should be tapered slowly if stopped, as withdrawal is common and can be prolonged.

Objective 4: Select the appropriate pharmacologic therapy for anxiety or depression based on key clinical features and patient preferences.

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors, particularly SSRIs, seem to have the best safety and tolerability profile, although the evidence for this is conflicting. Key factors to consider include cost, patient preference, prior response to medication, and side effects. The interactive table helps categorize medications on their defining features (activating/sedating) and common side effects, which can often be used as an advantage. To review these options, we offer three brief vignettes to highlight common clinical situations with a selection of the most appropriate agents.

Cases

Case 1: This case highlights a typical diagnosis and treatment of a patient with new onset depressive disorder. For screening, he should be screened with a PHQ-9 due to high clinical suspicion. Take note to tell your learners that the PHQ-2 and PHQ-4 are used for generalized assessments for all patients. Given this patient’s high clinical probability, we would recommend the PHQ-9. This screening form also highlights that screening tools are inadequate for diagnosing GAD and Depression. The next question in this case gives you an opportunity to discuss Suicide Risk Assessments (see below). This case concludes with starting a patient on medication based on general recommendations (SRI as first line) and side effects (avoiding paroxetine in the setting of increased appetite.

Safety Assessment

The ability to predict attempted or completed suicide is poor, however suicide risk assessments remains a critical aspect of treating depression. Many tools exist to assess suicidal risk, make sure to discuss your site’s current process.. Importantly, encourage your learners to use straight forward language when discussing suicide, i.e. ask “are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now?”, instead of “hurting yourself?”. Also note that asking about suicide does not increase the risk or rates of suicide. We recommend having learners discuss and develop screening questions that they have used or seen used.

Take-Home Points

-

- Do not use PHQ-4 or PHQ-2 when the probability for depression or anxiety is high. Use a more in-depth tool such as GAD-7 or PHQ-9.

- Familiarize your learners with screening for suicide risk factors.

- Use side effect profile to help pick initial medication treatment

Case 2: This case highlights the management of depression in a geriatric patient. The first question encourages learners to develop a broader differential for high-risk patients presenting with vague symptoms (fatigue and poor concentration). It also enforces that depression in the elderly often manifests this way. Again, learners will need to pick a first-line medication based on safety in the elderly and side effects. In this case, mirtazapine may be beneficial for weight gain effects. SRI’s are still first-line therapy for elderly patients and Citalopram is an appropriate choice given it has relatively few interactions with medications (as opposed to other SSRIs that inhibit Cyp P450). Finally, this case reminds learners of the delayed effect of antidepressant treatment, especially in the elderly. Likewise, it encourages learners to start low and go slow when starting antidepressant treatment in elderly patients.

Take-Home Points

- Think broadly about a differential for geriatric patients presenting with depressive symptoms or vague somatic complaints. Depression is especially common in patients following MI and stroke

- Use Citalopram in patients on several medications due to its low risk of med-med interactions

- Start low and go slow

Case 3: This case demonstrates a patient presenting with primarily somatic complaints, a common presentation of anxiety and depressive disorders. The first question should remind learners to consider substance use disorders that can contribute to anxiety and depression. In this case, the patient has mixed GAD and Unipolar Depression, another common presentation. The first-line treatment for both disorders is SRI. For this patient, her chronic pain may make an SNRI the appropriate first choice. While her chronic pain is likely worsened by her depression and anxiety, it’s important for learners to not discredit these symptoms. Physical therapy would be appropriate for this patient. Due to her refractory symptoms, she is switched to sertraline (a more stimulating SSRI). On her follow-up, the drastic improvement in her symptoms and increased energy may be due to a good response to sertraline but may be concerning for hypomanic episodes of unmasked bipolar disorder. This should prompt learners to rethink the diagnosis and do a careful assessment.

Handouts

Learner handout – Recommend printing out ahead of time and distribute to learners when you are ready to do pair-shares for the cases.

Presentation Board

Take Home Points

- PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are the preferred tools for diagnosis and monitoring response to therapy for Unipolar Depression and Generalized Anxiety Disorder, respectively.

- Short-term follow-up (within 2 weeks) of initiating a pharmacologic treatment of depression or anxiety is critical to avoiding severe complications and enhancing compliance.

- Selection of the appropriate SRI depends on comorbidities, patient preferences, side effect profile.

- Do NOT forget to treat somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety, I.e order physical therapy, discuss HA treatment, etc.

- Frequently monitor for signs/symptoms of other mental health disorders, including Bipolar Disorder.

References

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Aug 22;374(9690):609-19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5. Epub 2009 Jul 27. PMID: 19640579.

Gelenberg, A. J. et al (2010, October). Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. apa.org. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf.

Clinical Practice Review for Major Depressive Disorder. Clinical Practice Review for Major Depressive Disorder | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (n.d.). https://adaa.org/resources-professionals/practice-guidelines-mdd.

Clinical Practice Review for GAD. Clinical Practice Review for GAD | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (n.d.). https://adaa.org/resources-professionals/practice-guidelines-gad.

Lewis G, Marston L, Duffy L, et al. Maintenance or discontinuation of antidepressants in primary care. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1257-1267.

Lyness, J. M. (2020, December 28). UpToDate. Unipolar depression in adults: Assessment and diagnosis.

Craske, M., & Bystritsky, A. (2021, January 26). Approach to treating generalized anxiety disorder in adults.