Published November 2022

Authors: CJ Mowry, MD1; John Haydek, MD2

Section Editor: Elijah Mun, MD3

Executive Editor: Yilin Zhang, MD4

1 Resident, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado

2 Fellow, Department of Medicine – Gastroenterology, University of Colorado

3 Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Colorado

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Washington – Valley Medical Center

Objective(s)

- Identify the spectrum of alcohol related liver disease (ALD) and risk factors for developing alcohol related liver disease (ALD)

- Select diagnostic tests to differentiate between hepatic steatosis, alcohol-related hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis

- Develop a paradigm for managing the spectrum of ALD

- Diagnose and manage acute alcohol related hepatitis (AH)

Teaching Instructions

Plan to spend at least 10-15 minutes preparing for this talk by reviewing the teaching script and clicking through the graphic animations on the Interactive Board. The mouse icon indicates an interactive button. These may be used to navigate between pages or prompt a question for your learners. Print out copies of the Learner’s Handout so learners may take notes as your review the spectrum of alcohol related liver disease, diagnostic testing, and management.

The talk can be presented in 2 ways:

- Project the “Interactive Board” OR

- Reproduce your own drawing of the presentation on a whiteboard

The anticipated time to deliver this talk is 20 min without cases and 25-30 min with cases. Begin with reviewing the objectives for the session. We recommend progressing in order, although this gives you the flexibility of doing more focused teaching on subtopics of interest.

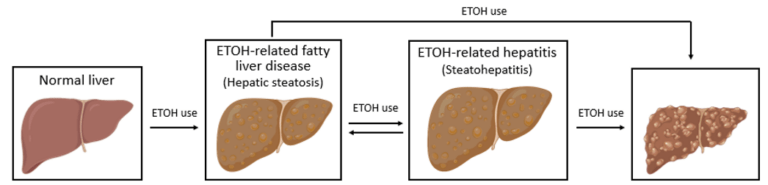

Click on each image to reveal the next stage in the spectrum of ALD.

- Alcohol-related hepatic steatosis is the earliest form of alcohol related liver disease and by itself is a benign entity that can regress with alcohol cessation. However, steatosis is indicative of alcohol-induced alterations in metabolism and suggests susceptibility to progression to more advanced liver disease with continued alcohol use. It is seen in ~90% of heavy drinkers.

- Alcohol-related steatohepatitis (ASH) is an inflammatory intermediary in the development of alcohol– related cirrhosis and can be present indolently, or fulminantly as acute alcoholic hepatitis. With alcohol cessation, ASH can improve although any underlying fibrosis caused by the inflammatory cycle will remain. The risk of developing cirrhosis is higher when ASH is present rather than simple steatosis.

- Alcohol-related cirrhosis is the end-stage byproduct of longstanding alcohol use brought on by the maladaptive response of the liver to scar (fibrosis) in response to inflammation. Alcohol-related fibrosis and cirrhosis is largely irreversible even with complete alcohol cessation.

Risk factors: Ask your learners what are risk factors for developing ALD?

Overall, rates of ALD are increasing worldwide in conjunction with increasing rates of alcohol use disorder (AUD). Risk factors include:

- Quantity of alcohol intake ≥2 drink/day (women), ≥3 drinks/day (men)

- Pattern of alcohol intake (e.g., recurrent binging increases risk)

- Genetic predisposition

- Obesity, women>men, smoking

- Concurrent liver disease

Objective 2: Select diagnostic tests to differentiate between hepatic steatosis, alcohol-related hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis (Diagnosis)

All adults with current or prior unhealthy alcohol use should be screened for ALD. Various questionnaires and risk scores should be utilized (e.g., CAGE, AUDIT-C) to screen for alcohol use disorder (AUD), although the presence of unhealthy alcohol intake alone is sufficient to warrant screening for liver disease.1

Initial screening typically consists of an ultrasound of the liver (RUQ US) along with basic labs consisting of complete metabolic panel (CMP), CBC, and INR. Of note, we use the term LFTs (liver function tests) for brevity and familiarity in our teaching materials to refer to liver enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP, etc). Liver enzymes is the more appropriate term as these enzymes do not measure liver function. Depending on results from these studies, additional testing may be warranted. Click on each of the diagnoses to reveal additional diagnostic work-up.

- Hepatic steatosis is defined histologically as the presence of fat (steatosis) on liver histopathology. Steatosis from alcohol use is indistinguishable from steatosis related to NAFLD on both histopathology and imaging, therefore, clinical history is paramount to clinch the diagnosis. Various imaging modalities (particularly US) may also show evidence of steatosis and hepatomegaly (from fatty infiltration of the liver). LFTs are classically normal in hepatic steatosis although with ongoing alcohol use it is not uncommon for LFTs to be minimally elevated, but should return to normal with alcohol cessation.

- Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a clinical syndrome with a distinct histopathologic correlate in alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH). ASH is defined histologically by neutrophilic lobular inflammation, ballooning hepatocytes (Mallory-Denk bodies), and peri-cellular fibrosis. The presence of steatosis on imaging in combination with elevated transaminases is suggestive of alcoholic steatohepatitis although biopsy is rarely performed to confirm the diagnosis in clinical practice. More information on the diagnosis and management of acute alcohol-related hepatitis is below.

- Alcohol-associated fibrosis and cirrhosis are the final stages in the spectrum of ALD and represent irreversible liver injury. While classically these were histopathological diagnoses, noninvasive testing has been increasingly used to support the diagnosis and obviate the need for liver biopsy. Blood-based biomarker risk scores such as FIB-4 and APRI (AST-to-platelet ratio index) have been validated for use in ALD and can be suggestive of advanced liver disease. Serologic risk scores such as FibroSure can also be used to determine likelihood for fibrosis. Additionally, advanced imaging including MRI can be utilized to evaluate for evidence of hepatic fibrosis and features consistent with underlying cirrhosis.6,7

Objective 3: Develop a paradigm for managing the spectrum of ALD. (Management)

There are several over-arching concepts when it comes to caring for a patient with ALD.

- Alcohol cessation – Complete abstinence from alcohol is the single most important factor for improving survival in ALD. With complete cessation, hepatic steatosis and inflammation can regress and progression of ALD can be slowed, although liver fibrosis is typically irreversible. In contrast, with continued alcohol consumption liver disease will almost certainly progress. While largely outside the scope of this talk, a multimodal approach to alcohol cessation including pharmacotherapy and psychosocial and behavioral treatments is most effective. All patients with advanced ALD and/or AUD should be referred to AUD treatment professionals. Ask your learners what pharmacotherapies and psychosocial treatments can be used for alcohol cessation.

- Medications – FDA approved medications for relapse prevention in patients with ALD are naltrexone and acamprosate and are considered first line treatments. Multiple non-FDA approved medications may have some benefit in relapse prevention such as gabapentin, baclofen, and topiramate. 1,3

- Naltrexone – opioid receptor antagonist and can be dosed daily (orally) or with monthly subcutaneous injections. It undergoes hepatic metabolism and can cause hepatotoxicity. It has not been studied in patients with alcohol-related hepatitis or alcohol-related cirrhosis.

- Acamprosate – NMDA receptor antagonist. Dosed orally three times daily. No reported hepatotoxicity but should not be used in patients with severe renal dysfunction.

- Of note, disulfiram is FDA-approved for AUD but not in patients with ALD.

- Psychosocial and behavioral therapies include referral to substance use disorder specialists, motivational interviewing, social support groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous), outpatient or residential sobriety programs.

- Medications – FDA approved medications for relapse prevention in patients with ALD are naltrexone and acamprosate and are considered first line treatments. Multiple non-FDA approved medications may have some benefit in relapse prevention such as gabapentin, baclofen, and topiramate. 1,3

- Nutrition – Patients with ALD, and in particular those who continue to consume alcohol, tend to have poor nutritional status and a healthy diet with appropriate vitamin supplementation is imperative. Guidelines recommend a high-protein diet for patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis or cirrhosis in combination with a low-sodium diet if stigmata of portal hypertension are present. Additionally, patients who continue to drink alcohol or those who recently attained sobriety should take a daily folic acid, vitamin B complex, and thiamine supplement. There is also data suggesting zinc supplementation may be beneficial, particularly in those with AH.

- Liver Transplant Evaluation – For those patients with alcohol associated cirrhosis who do not recover liver function with alcohol cessation, referral to a transplant hepatologist is appropriate to consider candidacy for liver transplant. Requisite criteria for liver transplant vary across treatment center. There are emerging data supporting liver transplantation in carefully selected patients with AH (and by definition <6 months sobriety), although there is limited adoption so far for this population.

Objective 4: Diagnosis and management of acute alcoholic hepatitis (AH)

Diagnosis1: Acute alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a subtype of alcoholic steatohepatitis characterized by a marked inflammatory state with the potential for multiorgan dysfunction. While AASLD guidelines suggest biopsy is required for AH, this is rarely performed in clinical practice and instead a clinical diagnosis with characteristic laboratory and history data can be utilized.

Clinical diagnosis:

- Heavy alcohol intake (≥3/day for women; ≥4/day for men) for a prolonged duration (≥60 days). A patient may have been abstinent prior to onset of jaundice/hyperbilirubinemia although period of abstinence should not exceed 60 days.

- Onset of jaundice within prior 8 weeks

- AST > 50, AST typically at least 1.5x ALT (and both values <400 IU/L)

- Hyperbilirubinemia with serum total bilirubin > 3.0 mg/dL.

Other clinical features that are often present include leukocytosis with absolute neutrophilia and RUQ abdominal pain (which is from tender hepatomegaly). Other potential symptoms include fever, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, anorexia, and muscle wasting/weakness. Concurrent infection is relatively common at time of admission for AH and should be evaluated for in every patient.

Management1:

- Establish disease severity. Various calculators are available to assist in determining severity (Maddrey discriminate function (MDF), MELD, Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS)) although the MDF is the most commonly utilized. MDF is calculated based on total bilirubin and INR, with a higher MDF score correlating with more severe disease and worse outcomes. An MDF ≥ 32 is the threshold for higher risk disease (corresponding to 14-50% 28-day mortality rate) and warrants considering of pharmacotherapy treatment based on prior studies in AH.9,10

- Treatment options:9.10 Various medications have been studied with prednisolone demonstrating the most convincing benefit.

- Prednisolone has demonstrated a short-term but not long-term mortality benefit, with the mortality benefit was only at 28-days from treatment initiation and not at longer follow-up periods. Notably, treatment with prednisolone is associated with increased risk of infection and use of corticosteroids is controversial with significant variability between medical centers on its use.

- Several relative contraindications exist for corticosteroid use in AH including: known infection, acute kidney injury (AKI) with serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL, multiorgan failure or shock, uncontrolled GI bleed, or suggestion of additional contributor to cause of liver injury. Presence of exclusion criterion should prompt general management of ALD as outlined below without additional pharmacotherapy or delay in initiation of corticosteroids until the contraindication resolves. Of note, AKI is a relative exclusion criteria because patients with AKI were excluded from most AH clinical trials. If AKI resolved, steroids should be reconsidered.

- If treatment with corticosteroids is pursued, the Lille coefficient can be calculated on day 4-7 of treatment to assess the change in bilirubin relative to several other factors, which can suggest early treatment response. A Lille score < 0.45 suggests benefit/improvement with corticosteroids and completion of the 28-day course is recommended. A Lille score ≥ 0.45 suggests lack of benefit and cessation of corticosteroids is recommended given risks outweigh potential benefit.11

- Smaller trials have also suggested short-term but not long-term mortality benefit from N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) although larger randomized studies are warranted prior to widespread adoption.1

Cases:

- Case 1 – Diagnosis and evaluation of ALD

- Case 2 – Diagnosis and management of AH

Take Home Points

- Alcohol-related, or alcohol-associated liver disease, is a spectrum of disease that ranges from asymptomatic alcohol-related fatty liver disease to alcohol-related hepatitis (AH), to cirrhosis.

- Alcohol abstinence is the single most important factor in improving survival in ALD. A multimodal approach to treatment including pharmacotherapy and psychosocial/behavioral interventions is most effective.

- Alcohol-related hepatitis (AH) is a clinical diagnosis characterized by elevated AST/ALT with ratio typically >2, Tbili elevation >3, recent heavy alcohol use, and recent onset jaundice.

- Prednisolone can be considered in patients with severe AH (MDF>32, MELD>20) without contraindications such as active infection or bleeding.

References

- Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, Mellinger JL, Lucey MR. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol‐Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71(1):306-333. doi:10.1002/hep.30866.

- Drinking levels defined. Accessed on November 29, 2022. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking#:~:text=NIAAA%20defines%20heavy%20drinking%20as,than%207%20drinks%20per%20week

- Holt, SR. Alcohol use disorder: Pharmacologic management. In Uptodate, Stein, MD and Friedman, M (eds). Waltham, MA. <Accessed on: November 29, 2022>

- Singal AK, Mathurin P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Jul 13;326(2):165-176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7683. PMID: 34255003.

- Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113(2):175-194. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.469.

- Thiele M, et al. Accuracy of the enhanced liver fibrosis test vs FibroTest, elastography, and indirect markers in detection of advanced fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1369-1379

- Lombardi R, et al. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015. 21(39): 11044-11052.

- McClain C, et al. Role of zinc in the development/progression of alcoholic liver disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2017; 15:285-295.

- Maddrey WC, et al. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1978. 75:193-199.

- Pavlov CS, et al. Glucocorticosteroids for people with alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11:CD001511.

- Garcia-Saenz-de-

Sicilia M, et al. A day-4 Lille model predicts response to corticosteroids and mortality in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:306-315